The Art of Educating a Human: Humanities for Our Times.

An access to "a reason for living" is, among us, the most important of the things we can receive from education

James V. Schall

In the misguided quest for relevancy and novelty, we forget that “education” means to draw out. That is, to show students new worlds, confront them with the sublime and the strange, sharpen their taste for beauty, refine their moral compass and deepen their judgment -- in short, to invite them into an examined life. Too much of contemporary teaching aims at the reverse: flattering the self (instead of coaxing them out of their adolescent selves), foregrounding topical issues without probing them deeply and focusing on skills rather than knowledge. The result: institutions across the United States that press critical thinking as an educational goal in itself -- critical thinking about nothing in particular.

Inside Higher Ed David Steiner and Mark Bauerlein

Beginnings

It’s been nearly nine years since we first lectured to a cohort of pre-med students studying for a medical entrance exam. To the soft whirr of the laundromat under us we quietly went from questioning existence to critiques of capitalism to the (back then) social phenomenon of the Brunswick hipster. Most of these students were from science and biomed backgrounds, with the odd born-again commerce or law student raising a hand here and there. What would begin as edutainment, slowly over the course of a few weeks would take shape in their minds as knowledge of the world they wished they had known sooner. This of course comes as no surprise to good teachers of any of the disciplines that make up the humanities; humans really need to know the humanities -- we’re in the word for a reason.

One of the things it means to know the humanities we would explain to our cohorts, is to know what furnishes the conceptual bedrock of all those ideas and ways of thinking that have come to characterise it, a genealogical origin that can be found foundationally in philosophy. To make clear the relevance of the humanities and its foundational discipline of philosophy we defined it in relation to something no one can avoid - life itself. The Roman philosopher Cicero provides us with the requisite definition: philosophy is the ars vitae - the art of living, and as pointed out by Elisabeth Lasch-Quinn “it presupposes inwardness -- the cultivation of an inner life -- and the centrality of the search for meaning as the paramount human endeavor.”. She goes on to tell us that “inwardness is the way the self develops the resources necessary for everything from enduring hardship to soaring to the heights of a fulfilled human life.” and finalises the point thus: “It is no luxury...The art of living is how we get along, how we get by, and why”.

To emphasise this is not to say that we all need to enroll in the arts and humanities, since for most of us what makes us human comes to us through means such as inherited tradition, participation in the debate on our social and political institutions (be it through running for parliament, or making tik toks), some modicum of human nature, and so on. These means however do not guarantee the formation of a full human, since we still have the radical skepticisms, nihilisms, materialist doctrines, and a whole host of the other isms of our times to contend with. These and more features of our time that make a study of the arts and humanities a necessary part of a good education will be taken up in a future post, and are dealt with in detail in our own courses. For now we’ll suffice with noting the integral place of the humanities in cultivating that state of inwardness necessary to the lifelong practice of investigating what it means to be human, and more importantly, the lifelong practise of being human.

For some - many more than we’d care to admit - the sessions did remain edutainment. I put this down to failures on our part, their part, and the bigger job-directed education of which we’re all a part (a topic in our crosshairs). For the rest, a constant of our teaching experience was the frequent request for a place or platform to study these ideas along with the gamut of ideas that make up the humanities more broadly; to study them for their own sake as much as for the palpable effect it has on the way we see and be in the world. These students expressed in their excitement the innate desire we all have to know, a desire already strong by virtue of our natural curiosity as strangers in our own world, and further exponentially strengthened the more we know - so, enter ‘First Philosophy’.

The Course and Contents

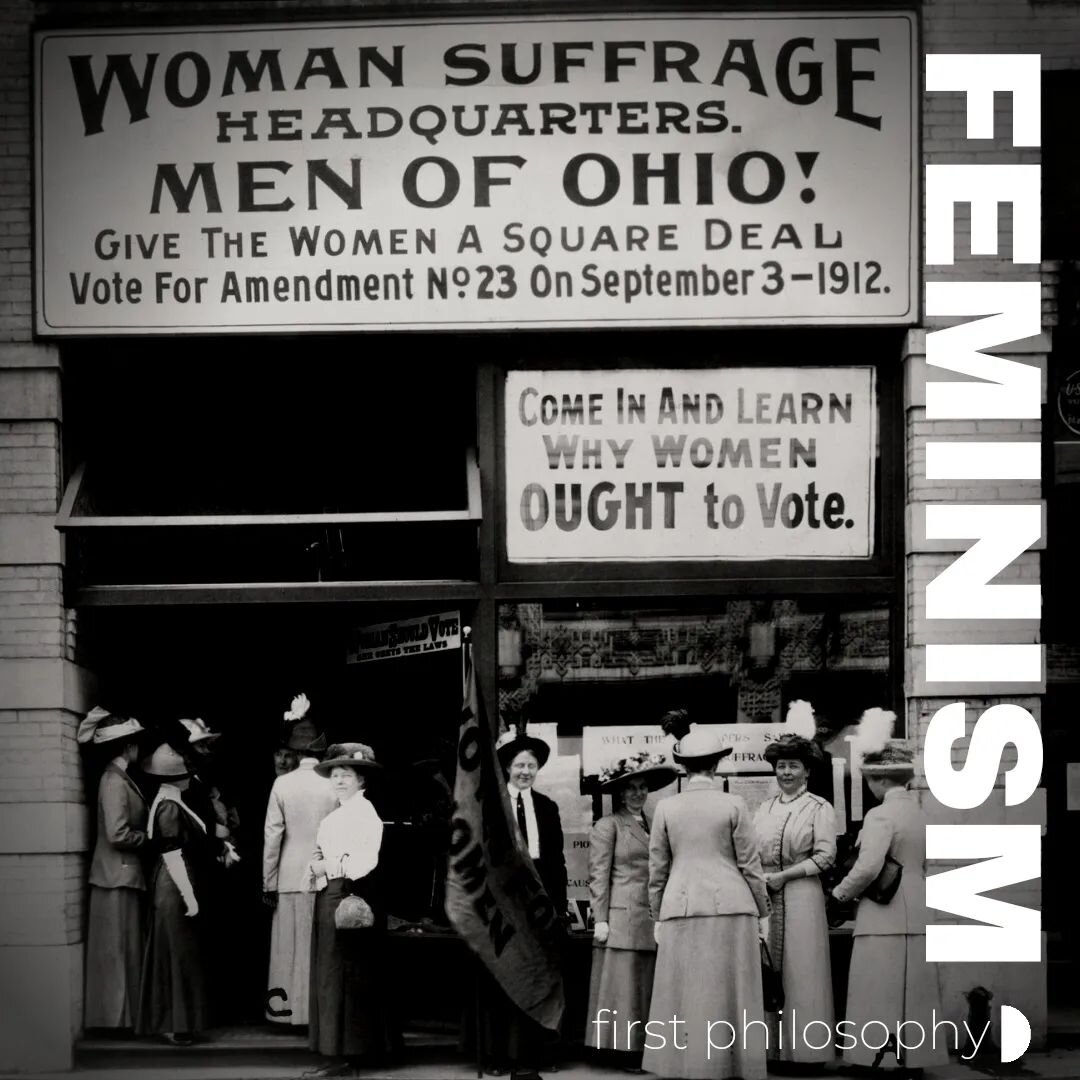

First Philosophy represents an attempt on the part of a few of us, old-school teachers, philosophers, lawyers, economists, social theorists, graduates of the arts, to answer the enthusiasm with which these stories and analyses of the human condition were sought by our students. It consists of a range of humanities courses we are curating for a wide variety of educational needs, all taught through two primary pedagogies. One of narratives: stories of our past, present and future - ‘The Human Story’, and one of ordered, systematic philosophy that takes certain key existential intuitions as starting points of inquiry - ‘first philosophy’.

Our pedagogies are informed by years of teaching this material to students with minimal prior exposure to the breadth and depth of the humanities. Excessive compartmentalisation of disciplines in our conventional learning institutions has led to a growing inability to see how things relate to one another, only worsened by a skepticism that things even relate to one another at all or to one another in ways that should interest and concern us. Add to this an apathy towards the question, spurred on by an apathy towards all such questions that don’t immediately lend themselves to our commercial and material advances, and we find ourselves in an educational and existential mess. Reflecting back to the early days, what captured student attention back then seems to have been a mix between the storytelling nature of our pedagogy, the sense of ‘some important knowledge’ to be had, and the way with which the everyday student’s everyday life was illuminated through an analysis of human affairs. In telling the human story they came to see, in however fragmented a manner, their own individual reflections, and so came to greatly value this activity which discloses to them knowledge of their own selves: knowledge of who, and what, and why they are, and why they are the way they are.

Teaching the humanities through the lens of ‘The Human Story’ lends itself nicely to a pedagogy of existential questioning, one at once systematised and given a rigorous intellectual framework as a first philosophy while remaining a thoroughly personal and individual journey. The task of good teaching is to set the student up on their own two feet in order that they become their own teacher and take control of their own learning. For this purpose, rooting students in universally accessible and deeply human existential intuitions we set them up for a course of inquiry that is unified in its beginnings and creates a common ground upon which the foundations of knowledge can be built. To this end, our first-contact questions with students are usually something of the form: how did we get here? And not only here, on this planet, in this world, but also here, in this society, wearing these types of clothes, speaking these languages, having these thoughts, and doing these things? Otherwise put: why is my life the way it is? And why should I care? The immediate practical relevance of this question for us is clear, for to ask this is to be able to ask: can my life be other than it is? The form of this question indicates agency: can my life be other than it is? The answer: yes, it can, but how? and: no, it cannot, because of these and those constraints. The more detailed the answer to this question the more capable we are of making our lives other than what it is now, and identifying that which hinders our capacity to do so. And thus in filling in this ‘howness’ through knowledge of the humanities, the arts, the social sciences, we are in fact strengthening our agency, our capacity to direct our lives as we see fit, and who wouldn’t want that? (perhaps, not many, it may be argued - let’s take that up in a future post). What makes this even more interesting is that even the desire to be able to direct our lives as we see fit grows from a deeper immersion into this sort of knowledge. When we come to terms with ourselves we see how valuable it is to value ourselves and the choices we make in the lives we lead, and when we come to terms with other people, we see how valuable it is to value them and to care about the choices they make in the lives they lead. A correct study of the humanities can truly have a humanising effect on the learner.

A complete education is a lifelong journey, one aptly characterised by education theorist Jacques Maritain as “the long historical and intellectual effort it takes to bring ''the human person, in woman as in man, to a consciousness of its dignity””.

Philosophy is the art of living

The art of educating a human and the art of living are two dimensions of one reality. To be educated is to be welcomed into a way of being where the way we are, our being human, becomes our primary concern.

Let’s finish with a return to Lasch-Quinn who aptly summarises the task thus:

“…perhaps the richest human conversation in which a person can take part. It is a conversation about how we should be living our lives, what the options are, and what is implied by the path we take. The conversation is open to us too, should we choose to partake. We have a standing invitation, just by virtue of having been born. Only by knowing the alternatives can we come to an understanding of how we live now— of what has led to this moment—and the choices we have for the future.”